Decision to use?

Reviewing the decision-making process behind the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

“Listen, Tom, if I’m going to kill 100,000 people, I’m not going to do it on verbal orders. I want a piece of paper.”

Gen. Carl Spaatz to General Thomas T. Handy, Deputy Chief of Staff of the US Army, who was giving him the order to deploy the atomic bombs over the phone.

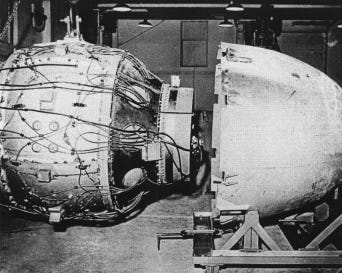

80 years ago, two atomic bombs killed 210,000 people1, mostly civilians, in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The morality of the bombings is still a topic of interest today. Polling firm Pew likes to ask Americans whether dropping Little Boy and Fat Man was justified when the anniversary of the bombings comes up. Academics have created an entire cottage industry around the question, with two broad camps: the traditionalists, who think that the bombings were justified because they brought the end of the war and avoided a bloody invasion, and the revisionists, who think otherwise. The debate is lively on social media and naturally organizes itself around those two camps2.

The objective of this article is to examine, based on the best available evidence, what drove the decision to drop two atomic bombs on Japan, whether our retrospective debates are well-founded, and what lessons we can learn from this. Specifically, I want to evaluate the decision-making process based on what leaders knew and how they reasoned at the time, not the consequences that followed. We judge the quality of the wager, not the luck of the outcome. Just because you did not kill anyone while drunk driving does not make drunk driving a good decision.

I believe this is the only good way we can reasonably evaluate the morality of the atomic bombings. The traditionalists and the revisionists argue in a purely consequentialist way, about whether the bombs caused Japan to surrender. But what occurred in the minds of the members of the Japanese Supreme War Council is irrelevant to the morality of the American bombing process that took place months before. What we should do is ask questions through a deontological, institutional approach: how was the decision to drop the atomic bombs reached? based on which information and using which reasoning? by whom? under which circumstances?

I argue that the atomic bombings were not the result of careful deliberations, and that President Truman, in particular, had little to do with it. The deeper problem is that the United States government was fundamentally confused about what the atomic bomb truly was. This is deeply problematic for the quality of the decision itself, and for us to evaluate this decision morally, using our modern conception of what a nuclear weapon is. We risk making a category error.

I owe a large intellectual debt to Michael Gordin, whose book “Five Days in August” is the intellectual backbone of the argument I make here, although I supplement it with extra evidence and citations taken from elsewhere. Please go read the book. I also want to thank Alex Wellerstein, whose presence online through the wonderful blog Restricted Data, as well as his serious historical writing, have both been extremely helpful in preparing this article.

Before Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Atomic Bomb is just a Weapon

There was no single, momentous decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. You heard that right: there was no debate among Truman and his staff, no reflection time, no sleepless nights, and certainly no red-button moment.

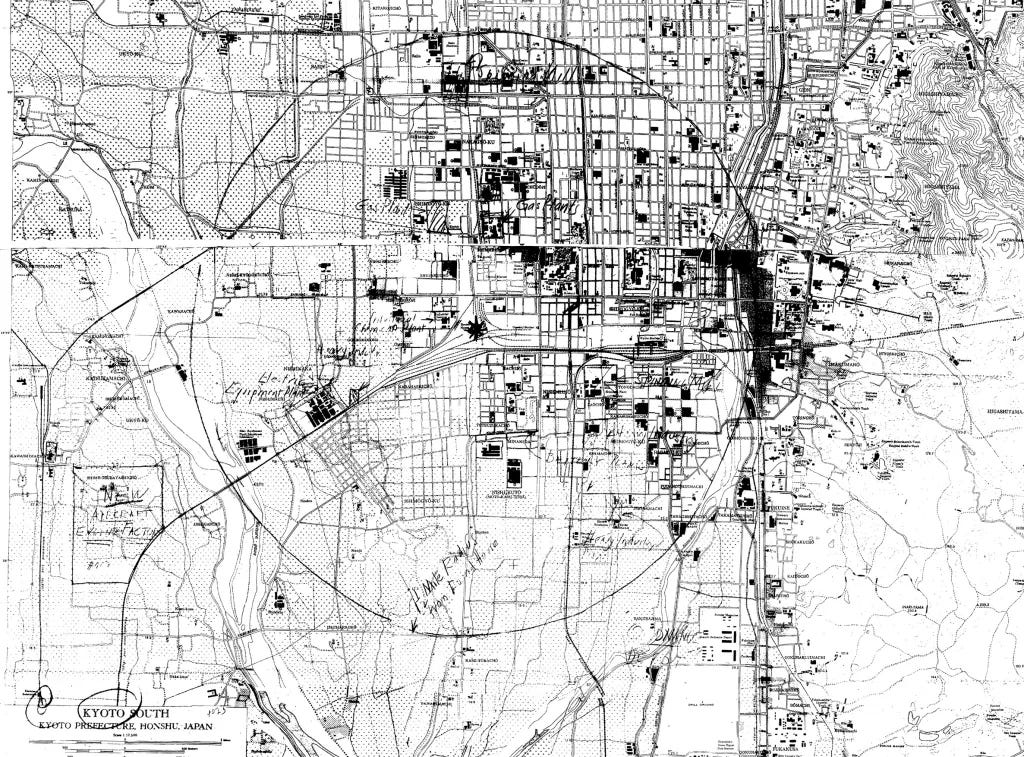

By 1944, it had become unquestioned policy that the atomic bomb would be used if it was ready before the end of the war3. This is not to say that no decisions were being made, far from it. Many decisions were being made, most notably by the blandly named Military Policy Committee, Interim Committee, and Target Committee, but they were questions of means: which enrichment strategies to prioritize, how to best use the bomb, on which targets, at which altitude, and to maximize which parameters. Even Secretary of War Stimson’s now-famous intervention to remove Kyoto from the list of targets was demonstrably not an intervention to halt or question nuclear bombing in general.

What about the big boss? Truman’s role in the deployment of the atomic bomb is best described as non-intervention. By the time of Roosevelt’s death on April 12, 1945, the Manhattan Project was progressing at full steam, under utmost secrecy. Truman, who had been kept in the dark as Vice President, was in over his head with learning the presidency on the job4. While we do know that he was briefed by his Secretary of War Henry Stimson and his Secretary of State James Byrnes, all available evidence shows that he had little input on the Manhattan Project, not that anyone really wanted him to be involved that late. Even dedicated haters like historian Gar Alperovitz, leader of the “revisionist” camp, struggle to find a single example of Truman being directly involved in anything5 related to the Manhattan Project prior to his order to stop the bombings after Nagasaki6. This quote from General Leslie Groves in his memoir “Now it can be told” really sums it up:

“As far as I was concerned, his [Truman’s] decision was one of noninterference—basically, a decision not to upset the existing plans.”

And the existing plans were progressing at a rapid pace, according to their own logic. The main limiting factor was not moral debates, but the supply of fissile materials. Throughout the first half of 1945, batches of plutonium and enriched uranium were steadily delivered to Los Alamos. By the time of Truman’s rise to power, the dangerous experiments to measure the critical mass of uranium-235 had just been completed. From there to Hiroshima, the project was in sprint mode.

Why it was in sprint mode in the first place is a good question to ask. After all, the project had been started by the fear of a Nazi atomic bomb7. By March 1945, Nazi Germany was on the verge of total collapse, culminating in its surrender on May 8th. The Alsos mission, tasked with gathering intelligence about the German atomic program in the wake of the Allied advance, had found conclusive evidence, by the end of 1944, that they were nowhere close to a working bomb8. By April 1945, Alsos had captured most of the German uranium, scientists, and hardware, which was at an embryonic stage comparable to that of the Manhattan Project in its 1942 exploratory phase. Conversely, while the Empire of Japan was still in the fight, no one in the US seriously considered the possibility of a Japanese atomic bomb; they were by and large correct9. Why go so fast, then?

Some authors like to call it “bureaucratic momentum”, but I just call it accountability to the taxpayer. Consider that the Manhattan Project had been a colossal expenditure of wartime resources. The specific figure of $2 billion (or the inflation-adjusted $27 billion equivalent) does not do it justice. It is better compared to other large military industrial endeavors of the time: the US Army spent about as much as it did on the Manhattan Project as it did buying B-17 bombers ($2.6 billion10), Sherman tanks ($1.6 billion11), or Thunderbolt fighters ($1.3 billion12). As a high-tech weapon program, it was twice as expensive as the proximity fuze that, by 1944, had revolutionized artillery tactics and was shooting down kamikazes and V-1s every day. Conversely, by April 1945, the Manhattan Project had nothing to show for all its billions. Once you strip hindsight bias, the glamour of Nolan’s Oppenheimer, and Surely You're joking, Mr. Feynman!, what do you get? A bunch of hyperspecialized chemical factories, and a ranch in the New Mexico desert with hundreds of eggheads on payroll, doing… what, to support the war effort, exactly?

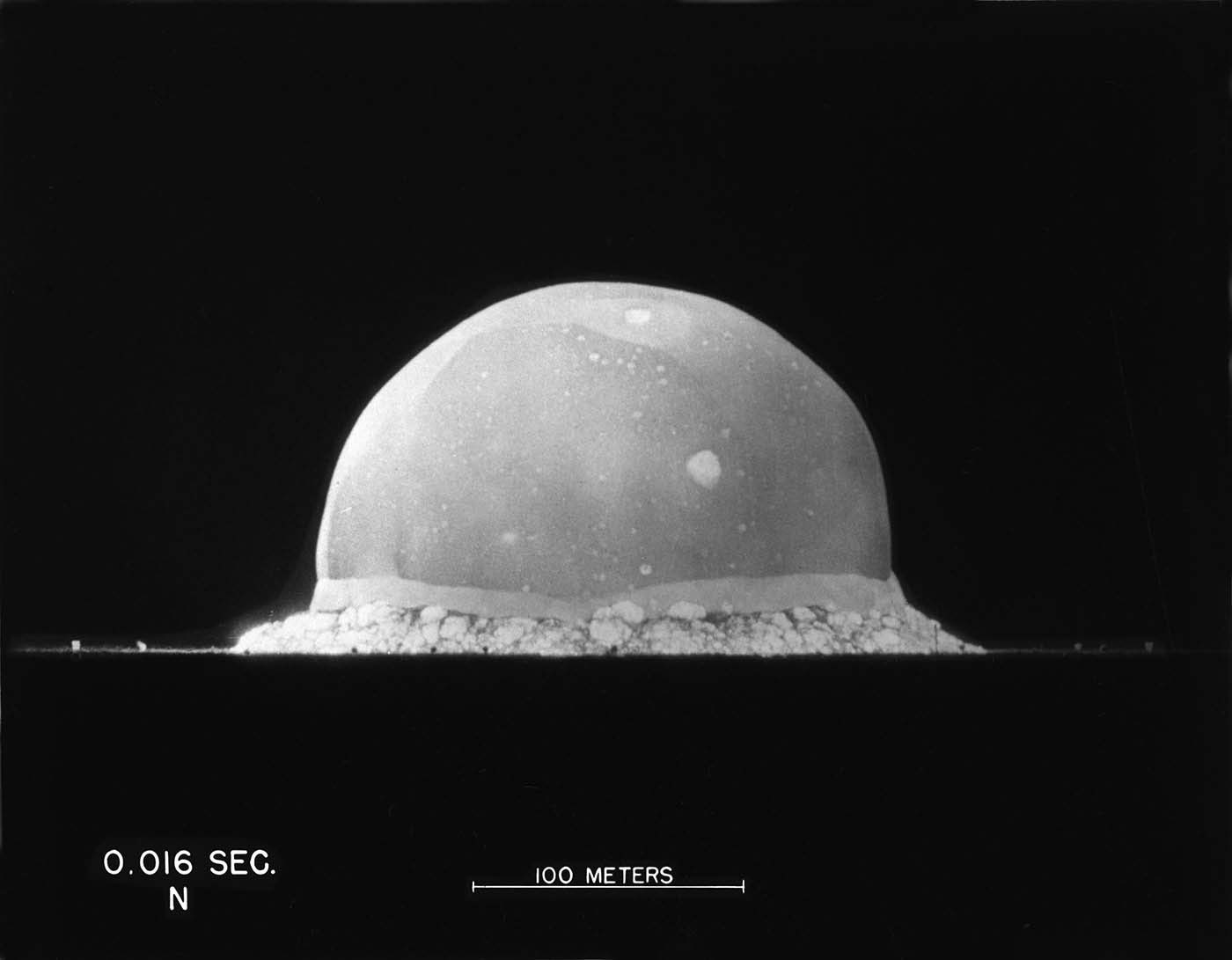

Even the bombs, in their undetonated state, were an insolent reminder of the absurdity of the project. A complicated gadget, that may or may not work, small enough to fit in a box truck, is somehow worth billions of dollars? It had become urgent for the Manhattan Project to justify itself through wartime use. Incinerating rattlesnakes and jackrabbits, as Trinity had done, was not going to cut it. Every day that passed without the bomb on the battlefield made it more likely that the Manhattan Project was going to be remembered as the greatest military boondoggle of the war, and perhaps of American history.

Groves, among other insiders, was deeply worried about appearing in a postwar Congressional hearing to explain how exactly he spent those billions of dollars13. He even commissioned an enormous steel containment vessel, called Jumbo14, to recover the Gadget’s plutonium, in case Trinity fizzled. But Trinity succeeded. If you have any doubt about how the main Manhattan leaders felt about the pressure of accountability, here is what Stimson said to his aide Harvey Bundy after learning of the success of Trinity: “I have been responsible for spending two billions of dollars on this atomic venture. Now that it is successful I shall not be sent to prison in Fort Leavenworth.”15 Alternatively, in his famous 1947 Harper’s article, in more diplomatic terms: “The entire purpose was the production of a military weapon; on no other ground could the wartime expenditure of so much time and money have been justified”16.

Behind this pressure lies a deeper revelation: the pre-Hiroshima atomic bomb was special, but not that special. To be precise, in the words of Michael Gordin, there was at the time a “tension between these two ways of looking at the atomic bomb: as world-shaking event or as tactical tool.”17 The “tactical tool” view explains much of the decision-making around the atomic bomb, culminating in its operational employment. To many actors, it was a high-tech weapon, like the proximity fuse, the radar, or early jet fighters, that was hoped to enable military success. And military success comes from using weapons, not keeping them in reserve.

The deployment order itself is illustrative. While requiring a direct order to deploy a weapon is somewhat unusual by WW2 standards, this specific order misses the gravitas that we would expect of an “order to use an atomic bomb” by many marks. First, if we trust General Spaatz, it was supposed to be delivered orally over the phone. He had to insist to get it in writing, leading to the quote that opens this article18. Secondly, it does not come from the President, but from the acting Army Chief of Staff, General Thomas T. Handy. And finally, it is not an order to bomb a specific target, but rather four, in no particular order of priority, constrained by atomic bomb supply: “Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki”. How special does that sound? The DOE archive website, tellingly enough, feels the need to specify that “Truman, of course, provided the ultimate authorization for dropping the bomb”. Did he?

The supply constraints mentioned by Handy’s order (“additional bombs will be delivered on the above targets as soon as made ready by the project staff”) reinforce the business-as-usual nature of bomb use. Far from the common myth propagated by Truman in his memoirs, that the two bombs were a deliberate choice to bluff the Japanese into surrender, the truth is that two bombs were used because two bombs were available. No one expected such a quick surrender at the time, and in fact, the Manhattan Project crew on Tinian spent the two days following Nagasaki in a feverish flurry of activity, preparing for a third shot that never came19.

The Nagasaki mission itself was improvised on the fly in a way that would be routine for a conventional bombing run, but sounds utterly unacceptable for our modern conception of what an atomic bombing mission should be. Plagued by operational delays, aircraft malfunction, and bad weather, the Bockscar crew almost disobeyed the direct order of dropping the bomb by visual sighting, not radar, because they did not have enough fuel to come back to base with the bomb20.

Consequently, most of the US military brass were distinctly unimpressed by claims that the atomic bomb had single-handedly ended the war. After all, this high-tech gadget was merely an improvement on what they had been busy doing for months: incinerating (for the Army Air Forces) and starving (for the Navy) Japanese civilians. We can trust here the work of Alperovitz, who compiled the most ambivalent reactions to the bombing in his effort to disprove the traditionalist narrative of “military necessity”21. None of those were middling bureaucrats protecting their turf, by the way. LeMay, Arnold, Nimitz, Halsey, were the top leaders prosecuting the war with Japan.

“ LeMay: The war would have been over in two weeks without the Russians entering and without the atomic bomb.

The Press: You mean that, sir? Without the Russians and the atomic bomb?

LeMay: The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.”

— Press conference by General LeMay, 1945

“From the Japanese standpoint the atomic bomb was really a way out. The Japanese position was hopeless even before the first atomic bomb fell, because the Japanese had lost control of their own air”

—New York Times interview of General Arnold, 1945

“The atomic bomb merely hastened a process already reaching an inevitable conclusion.”

—Speech to the National Geographic Society by Admiral Nimitz, 1946

“The first atomic bomb was an unnecessary experiment ... It was a mistake to ever drop it. Why reveal a weapon like that to the world when it wasn't necessary?... [the scientists] had this toy and they wanted to try it out. So they dropped it… It killed a lot of Japs, but the Japs had put out a lot of peace feelers through Russia long before.”

—Public statement of Admiral Halsey, 1946

What did they think was going to happen?

Not everyone was as dismissive of the bomb’s importance as those generals and admirals. Some decision-makers did grasp its exceptional nature and might, under the right circumstances, have been able to make an informed decision about the bombing. Yet none could predict the fundamental shift that Hiroshima and Nagasaki would have in elevating the bomb from a “tactical tool” to a “world-shaking” development, particularly for geopolitics and military affairs. What we observe is a highly variable degree of understanding, ranging from quite prescient to completely oblivious to the basic facts of the matter.

Stimson's case is particularly revealing. He had a background in foreign policy and had been involved in the project for long enough – since the beginning, in fact – to understand reasonably well its implications. But even if he clearly grasped that the bomb was more than a tactical tool, his memorandum of April 194522 to newly appointed President Truman, which should be a distillation of months of careful thought, gets a lot of things wrong.

The memo consistently emphasizes who possesses the weapon (the US), how long that advantage might last (a few years at least) and insists that the bomb could enable smaller nations to "conquer" larger ones through surprise attacks. Although the word is not used, Stimson is clearly worried about an arms race, but his framing treats the bomb primarily as an instrument of war-fighting and territorial conquest: there is no mention of mutually assured destruction or nuclear deterrence. The primary concern is that the weapons will be used, and what the consequences of their use would be. He does not imagine that restraint will be the dominant consideration of the atomic age.

On nuclear Armageddon itself, while Stimson mentions that “modern civilization might be completely destroyed” by atomic bombs, the rest of the memo makes it clear that it is not a physical destruction he is concerned about, but a moral one. Stimson fears that such powerful weapon would lead to a sort of Hobbesian state of nature among nations, a war of all against all: “The world in its present state of moral advancement compared with its technical development would be eventually at the mercy of such a weapon”. The idea that atomic bombs might become an existential threat to the survival of humanity itself is distinctly not here.

The scientists opposing the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki fared much better in terms of prescience, but the devil is in the details. The Franck report, and the accompanying Szilard petition, recommended a demonstration shot in an uninhabited location instead of a first military strike. They correctly understood that “we cannot hope to avoid a nuclear armament race, either by keeping secret from the competing nations the basic scientific facts of nuclear power, or by cornering the raw materials required for such a race.” They predicted perfectly well the dynamics of the Cold War: the Soviet Union would only need 4 years to catch up with the United States. This delay was mostly a matter of gathering enough fissile material, with espionage playing a limited role in accelerating the process23.

Their proposal of “international agreements on prevention of nuclear armaments” backed by “actual and efficient controls” to avoid “total mutual destruction” is, unquestionably, how things should have been done24. Importantly for us, they clearly understood that dropping nuclear bombs should not be business-as-usual: “the question of the use of the very first available atomic bombs in the Japanese war should be weighed very carefully […] by the highest political leadership of this country”. But exactly like Stimson, the emphasis of the Franck report is on the danger of active nuclear use. The idea that two nuclear-armed nations might exert restraint to avoid mutual destruction did not occur to the authors.

Their assessment that “in no other type of warfare does the advantage lie so heavily with the aggressor” simply did not stay true. The first technological scramble of the atomic age was precisely the development of second-strike capabilities: things like submarine-launched ballistic missiles, early-warning radars, and airborne command centers. Even the “infernal machines” mentioned in the report, nuclear weapons smuggled into an adversary’s city and remotely detonated, are only conceived as offensive tools, while later examination of the concept after the Cold War saw them as perfect second-strike tools25.

At the other end of the spectrum, Truman himself appears to have been fundamentally misinformed about what the bombs truly entailed. In his article “The Kyoto Misconception: What Truman Knew, and Didn’t Know, About Hiroshima”, Alex Wellerstein argues that Truman simply did not understand that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were cities full of civilians. He appears to have been convinced that they were legitimate military targets, learning only after the fact that they were not. Consider that both his public radio statement after Hiroshima and his private, personal diary, in which he had no reason to mislead anyone, refer to Hiroshima as a “military base”, and a “purely military [target]” so that “soldiers and sailors”, “not women and children” would be the victims, respectively. Wellerstein further points out that Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace recorded in his diary that Truman had justified his order to stop bombing because “the thought of wiping out another 100,000 people was too horrible. He didn’t like the idea of killing, as he said, ‘all those kids.’”.

Truman's post-facto learning wasn't unique among officials. The military had wide latitude on the conduct of the war, and civilian officials were rarely consulted on operational matters. At least once, Stimson learned of a firebombing campaign in the newspapers like everyone else, and was furious not to have been consulted26. Truman wasn’t alone either in hoping that the atomic bomb could be used on a military target. The first mentioned possible atomic target, in a 1943 meeting of the Military Policy Committee, was Truk Harbor (now Chuuk Lagoon), the major Japanese naval base in the South Pacific theater, essentially their Pearl Harbor. But by 1945, the Japanese fleet had ceased to be militarily relevant, and Truk posed no threat27. The only suitable targets left were cities, cities specifically spared from firebombing to offer pristine before-and-after comparisons of atomic bombing.

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Atomic Bomb is not a Weapon

What those testimonies show us is that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki created the ontology of the atomic bomb: they solidified its uniqueness as a strategic weapon, established its horrific effects for all to see, and firmly created the idea of the nuclear taboo in the public mind. This shift makes the mindset of the decision-makers difficult for us to reach today. We retroactively apply a teleological lens, where the bombs are immensely important, morally charged weapons before they were even used. As we have seen, this was not how decision-makers thought, or at least acted, toward the bomb before Hiroshima.

The strategic value of the bomb is forever tied to the near-immediate Japanese surrender. The apparent causal link is simply too strong: what do you mean, the bombs didn’t end the war? How can we explain that Japan accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration the day after Nagasaki, and formally surrendered a week later?

Explaining why this causal link is spurious is the whole shtick of revisionist historians like Alperovitz. They correctly point to the dismissive feelings of US military leaders, which we examined earlier. They also point to the simultaneous Soviet invasion of Manchuria. But their favorite activity is to dissect the diplomatic minutiae of the Potsdam Declaration and the palace intrigues leading to the Japanese surrender. They work very hard to connect everything in the Potsdam Declaration to the atomic bomb, and to sever any connections in the Japanese surrender to the atomic bomb. This delicate dance is necessary to present Hiroshima and Nagasaki as pure acts of “atomic diplomacy” meant to impress the Soviets, disconnected from any military necessity.

Our discussion of bomb ontology can mostly bypass that diplomatic nitpicking. We can remark that the Potsdam Conference had essentially no effect on the operational realities of bomb deployment: everything (fissile material production, bomb shipment to Tinian, 509th bombing group operations) kept going as planned, i.e. as fast as possible. To quote Michael Gordin again: “only a coincidence of timing linked the atomic bomb to the Potsdam Declaration; of the many possible shocks proposed, it proved the only one available that met the planned schedule for the end of the war”28.

As for the Japanese decision to surrender, we should remark, as alluded to in the introduction, that it is causally irrelevant to the decision to drop the bomb, since, well, it happened after the bombs were dropped. Our question isn't whether the bombs ended the war, but whether decision-makers expected them to end the war when they authorized their use. And as we have seen, they didn't. Atomic bombs only became war-ending weapons once the war ended.

Where Hiroshima and Nagasaki provided unusual clarity, however, was not in ending the war, but in demonstrating the moral horror of strategic bombing. It has become somewhat mundane to remark that the atomic bombings were not much more destructive than the conventional raids on Dresden, or Hamburg, or Tokyo. What this analysis misses is that the atomic bombs completely flipped the moral center of gravity. Prior to Hiroshima, decision-makers thought atomic bombs were morally acceptable because their effect would be similar to firebombing; after Hiroshima, firebombing became unacceptable because it was too similar to atomic bombing. While widespread firebombing against civilians did take place later during the Korean War, and to a lesser extent during the Vietnam War, the moral shift meant that proudly endorsing a “dehousing operation” was now off the table. Military commanders had to find suitable euphemisms: "supply centers," "communications centers," "enemy-held buildings", and stretch them like taffy to hide the fact that they were, in fact, firebombing cities.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki were also the first demonstrations of the radiation effects of atomic weapons. The Manhattan scientists consistently underestimated prompt neutron radiation and fallout: they initially dismissed Japanese radio reports of radiation sickness as “Tokyo Rose” propaganda29, and their own cavalier attitude toward radiation safety would prove fatal during the Demon Core incidents30, only two weeks after Nagasaki. But the fear of an invisible, lethal poison contaminating the land for centuries would prove to be the most enduring part of nuclear warfare in the public mind. Other practical features of atomic explosions cemented their uniqueness: the human shadows etched in stone, the mushroom cloud, the venomous, surreal colors of the fireball that photographic film fails to render but that many witnesses mention31.

All of this created the impression that the atomic bombings were a catastrophe that should never happen again, in complete contrast with the pre-Hiroshima zeitgeist where managing future atomic attacks was the dominant concern. The first Soviet nuclear explosion in 1949, and the ensuing arms race and equilibrium of terror, solidified the moral concern into a simple, practical matter of survival: nuclear Armageddon became a distinct possibility.

A catastrophe naturally calls for explanation, responsibility, and assurances that it will not happen again. In the years following 1945, the men involved, and the United States government itself, worked diligently, and often self-servingly, to provide all three.

We meant to do that in Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Our analysis has shown that under an institutional lens, the moral justification around Hiroshima and Nagasaki becomes, well, a bit thin compared to the two hundred thousand dead civilians it had to explain. Bureaucratic pressure and sunk-cost fallacy are never a good recipe for decision-making, regardless of the actual payoff. What the Truman administration did to square this circle was perhaps the most successful PR coup of the 20th century. DC and Marvel couldn’t have gotten away with this amount of retconning.

First was the question of responsibility. Truman recognized, quickly, that the Franck report was right and that he had been wrong. The minutiae of atomic bombings should not have been handed to a pair of committees: it should have been his decision. So, he just started taking credit for it. The absence of contemporary, direct evidence of his involvement gets plastered by bold-faced affirmations, for example in his 1955 memoirs: “The final decision of where and when to use the atomic bomb was up to me. Let there be no mistake about it.”, “I had made the decision.”. Nevertheless, he had to concede that “General Spaatz, […] was given some latitude as to when and on which of the four targets the bomb would be dropped. ‘That was necessary because of weather and other operational considerations.”, reluctantly recognizing that ultimate operational authority was delegated to military command.

We can hypothesize that this initial move was an easy source of legitimacy for Truman, an unelected president succeeding one of the most popular statemen of all US history. Truman had been a senator from Missouri and had made a name for himself investigating waste and fraud in Home Front projects. He was, as we have seen before, very inexperienced in many aspects of the presidency, including foreign policy. This was also convenient for everyone else. The people who had actually taken the decisions that mattered on the Manhattan Project, people like Vannevar Bush and James Conant, brilliant administrators as they were, probably recognized in hindsight that it should not have been up to them. So, they let Truman take all the credit for one of the most famous events of all time.

Secondly was the question of explanation. If dropping the bomb had been a decision by Truman, he needed a good reason for it. Here, we must thank Secretary of War Stimson, for his eloquent and profoundly misleading 1947 article in Harper’s titled “The decision to use the atomic bomb”, which successfully solidified the invasion myth in public consciousness for the coming decades. Here, Stimson argues that the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was the result of careful consideration of alternative options to force a Japanese surrender. Stimson boils down the options to a full amphibious invasion of the Japanese mainland, known at the time as Operation Downfall, which would have been guaranteed to be a bloody affair indeed, with up to a million US casualties alone. This was a deliberate PR strategy: the article was coordinated, under James Conant’s advice, with a near-simultaneous article by MIT President and Interim Committee member Karl T. Compton in The Atlantic, arguing along the same lines32.

The revisionists have picked apart this line of reasoning to death, and by this point in our article, we hope to have demonstrated that the idea that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the result of a carefully elaborated strategy is plainly untrue. If you had any doubt left about it, Barton Bernstein puts the final nail in the coffin. He found that one of the ghostwriters of the Harper’s article, Stimson aide Harvey Bundy (the same one from the Leavenworth quote earlier, yes), said in 1988 that the A-bomb decision did not involve an effort “as long or wide or deep as the subject deserved” and that Stimson had “claimed too much for the process of consideration” leading to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We will simply point out that Stimson’s own supporting documents quoted in Harper’s undermine the idea of a special atomic strategy but perfectly support the “tactical tool” thesis. He cites his own diary, on June 19: “the last chance warning . . . must be given before an actual landing of the ground forces in Japan, and fortunately the plans provide for enough time to bring in the sanctions to our warning in the shape of heavy ordinary bombing attack and an attack of S-1 [atomic bomb].” Here, we see that atomic bombs are not distinguished, and one might say, are equated with conventional firebombing. So much for special weapons.

Third, was fixing the command structure so that an unauthorized nuclear strike would never happen again. This process would have to be, at minimum, an implicit rebuke of the wartime structure of the Manhattan Project. The problem was that the bombs had been developed, fabricated, and operated completely under the control of the military. Civilian intervention, by Truman or Stimson, was fundamentally an intrusion in a self-contained, well-oiled machine running for its own reasons. The solution adopted by the Truman administration as part of the 1946 Atomic Energy Act was to wrestle nuclear weapon control from the military almost completely. The US military would therefore be merely operating nuclear weapons developed by and under the custody of a cabinet-level civilian structure: the Atomic Energy Commission, or AEC. While admirably bold, this arrangement proved too rigid for the demands of the Cold War, and soon enough military entities, like the Strategic Air Command and the Navy’s submarine fleet, had both custody and operational control of a wide range of nuclear weapons33.

The tug-of-war between civilian and military control of the nuclear arsenal ebbed and flowed during the Cold War, from Eisenhower’s broad delegation under New Look to Kennedy’s tighter leash, but it remained a live wire in civil-military relations until the deployment of Permissive Action Links (PALs). Invented in the 1960s, those sophisticated locking devices prevent nuclear weapons from being armed until they receive the Presidential activation codes, firmly putting the weapons back into civilian control. The military, of course, hated this. They opposed them at every turn, dragged their feet to disseminate and install them (three decades to fully equip the US nuclear arsenal), and might even have actively subverted them: SAC reportedly set the Minuteman launch codes to all zeros for decades, fearing it would not receive the presidential activation codes in time during war. But preventing the possibility of unauthorized use, à la Dr. Strangelove, was simply too important, and PALs were eventually installed on all weapons in the US arsenal by the end of the 80s. Nuclear weapons were, at last, no longer weapons like any others.

A conclusion

When viewed through Michael Gordin’s lens, through the lens of institutional decision-making rather than crude consequentialism, the atomic bombings are no less horrifying than before. But the horror shifts from the hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties, to the sheer absurdity of the bombing itself. The United States deployed a weapon it did not understand through a process that can best be described as a non-decision, a series of bureaucratic hoops that, perhaps adequate for conventional technology, proved to be a colossal mistake in the case of Fat Man and Little Boy. This original error was so great that the ensuing decades of US nuclear policy and public debate can be understood as an attempt to correct this original sin, and to justify what really happened, to find somewhere a moral decision that could be at least commensurate with the enormity of what occurred in August 1945.

But we cannot, in good faith, pretend that anyone made any decision that was even close to commensurate. No one can claim moral ownership of Hiroshima: the best they can say is that it happened under their watch. And while some of this was due to strategic short-sightedness and inadequate institutional design, our examination seems to show something far more troubling: no one, not even the best informed, or the most thoughtful, completely understood what the bombs were until they were dropped on Japan. Hiroshima created the bomb as we know it: a city destroyer, an invisible killer, a swallower of civilization. The bomb before Hiroshima was a different bomb, a theoretical bomb, a construct made of possibilities and risks.

This is not the conclusion I was hoping for. I hoped to find an interesting institutional tactic or architecture, a one weird trick that could have led the scientists from the Franck report to successfully make their case, to allow the Baruch plan to succeed before it existed, something that would give us hope in the age of AI and biotechnology. I found none of that. We might have had clean warning shots of pandemic hazards during SARS or the avian flu, polished, well-informed warnings made by talented filmmakers in Contagion, but in the end, it did not matter: COVID hit like an eighteen-wheeler all the same, and created its own ontology on the fly. When the AI catastrophe occurs, will the reports of the Future of Humanity Institute be of any help, in any sense of the word?

Counting the fatalities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is itself a highly contentious subject. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientist article on the topic, while certainly not a neutral source, contains a wide range of figures, from a low of 110,000 deaths, from the 1946 Manhattan Project report, to a high of 210,000 asserted by the Japanese-led 1977 “International Symposium on the damage and after-effects of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki”. I have not explored those questions in any depth. I use the 1977 higher estimates out of intellectual caution, but be aware that like the rest of the bombings, this is debated and debatable.

An example among many: leftist youtuber Shaun adopts a classic revisionist posture in his popular video on the topic, so brace yourself for a lot of discussion of the agenda of the Japanese Supreme War Council (sigh).

From “Now it can be told”, by General Leslie Groves, Chapter 19:

“Certainly, there was no question in my mind, or, as far as I was ever aware, in the mind of […] any […] responsible person […] that we were developing a weapon to be employed against the enemies of the United States. The first serious mention of the possibility that the atomic bomb might not be used came after V-E Day […]”

From “Prompt and Utter Destruction” by J. Samuel Walker, Chapter 1, page 7:

Truman’s doubts about himself were reflected, indeed magnified, in the views of other government officials and the American public. The president was, through no fault of his own, ill-informed and poorly prepared for the responsibilities he assumed. Roosevelt had not confided in him or attempted to explain his positions on key policy questions.

Feel free to read all 900 pages of Gar’s doorstopper magnum opus “The decision to use the atomic bomb and the architecture of an American myth” for yourself. He really did look!

One notable exception: he personally approved Stimson’s removal of Kyoto from the list of atomic targets.

As Alex Wellerstein did himself in his excellent article “Would the atomic bomb have been used against Germany?”, I looked into memoranda written by Vannevar Bush to Roosevelt during the early days of the Manhattan Project. I couldn’t find the same as him, but this cool nugget, dated from 16 December 1942, more or less say the same thing:

We still do not know where we stand in the [atomic] race with the enemy toward a usable result, but it is quite possible that Germany is ahead of us and may well be able to produce super-bombs sooner than we can.

From “The Making of the Atomic Bomb” by Richard Rhodes, Chapter 17, p. 606-607:

One of the most significant [Alsos leads] pointed to Strasbourg, the old city on the Rhine in Alsace-Lorraine, which Allied forces began occupying in mid-November […] Pash found a German physics laboratory installed there in a building on the grounds of Strasbourg Hospital. […] It is true that no precise information was given in these documents, but there was far more than enough to get a view of the whole German uranium project. […] The conclusions were unmistakable. The evidence at hand proved definitely that Germany had no atom bomb and was not likely to have one in any reasonable form.

From “Japan’s secret war: Japan's Race Against Time to Build Its Own Atomic Bomb” by Robert Wilcox, in the introduction, on p. 17. (the book is kind of a sensationalist rag, but it is well-sourced):

While American authorities always maintained the Japanese had neither the talent nor the resources to make a bomb, they had nevertheless sent a special investigating team into Japan right after its surrender to find out if they were right. The team concluded they were.

Otherwise, Richard Rhodes’ “Making of the Atomic Bomb” got you covered on p. 580:

Progress toward a Japanese atomic bomb, never rapid, slowed to frustration and futility across the middle years of the Pacific war.

From “The US Army Air Forces in World War II”, by Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate. Volume 6 “Men and planes” reports both production volumes and unit costs for most US military aircraft on pp. 354 and 360 respectively. I am using the 1944 B-17 production cost of $204,370 and the total production run of 12,677 aircraft for a total of $2.6 billion. This is a lower-bound estimate, since the unit cost decreased over time.

The unit cost of a Sherman tank is rounded to $60,000 from the contract values of M4 Lend-Lease shipments cited in the relevant table in “Statistical Review of World War II”. Given that 49,200 Shermans were produced, of which 22,500 went to Lend-Lease, according to p. 526 of “Sherman: a history of the American medium tank” by R.P. Hunnicutt, that gives a grand total of $1.6 billion for US-operated Sherman tanks.

Same source as for the B-17, which reports a 1944 unit cost of $85,578 and a production run of 15,579, for a total of $1.3 billion. Again, the unit cost decreased quite a bit over time, so the real figure might be a couple hundred millions higher.

From “Now it can be told” by General Leslie Groves, Chapter 6:

[A nuclear accident at the plutonium production plant] undoubtedly and quite properly would have resulted in a Congressional investigation to end all Congressional investigations.

I mention this last consideration only because, while we never gave any serious thought to it, it did give rise to a number of jokes during an otherwise deadly serious effort. I knew, as did Bush and Conant, as well as the President, Secretary Stimson, General Marshall and General Somervell, that if we were not successful, there would be an investigation that would be as explosive as the anticipated atomic bomb. Once, in 1944, Somervell told me with a perfectly straight face, at least for the moment: “I am thinking of buying a house about a block from the Capitol. The one next door is for sale and you had better buy it. It will be convenient because you and I are going to live out our lives before Congressional committees.”

A similar line of reasoning appear on p. 638, Chapter 18 of “The Making of the Atomic Bomb”, in an excerpt of an otherwise fascinating discussion between Leo Szilard and James Byrnes on the topic of atomic bomb use:

“[Byrnes] said we had spent two billion dollars on developing the bomb, and Congress would want to know what we had got for the money spent. He said, "How would you get Congress to appropriate money for atomic energy research if you do not show results for the money which has been spent already?""

Byrnes himself is an interesting character, and I do want to give him a closer look at some later times. While he is the main villain of revisionist works emphasizing “atomic diplomacy”, since his main contribution at the time was accompanying Truman at the Potsdam Conference and dealing with the Soviets as Secretary of State, our investigation focuses on the decisions taken not in Potsdam, which I believe was far more relevant to the actual process leading to the bombing.

From “Now it can be told”, by General Leslie Groves, Chapter 21:

We thought then that we might want to explode the first bomb inside a container, so that if a nuclear explosion did not take place or if it was a very small one, we might be able to recover all or much of the precious plutonium. […] Consequently we ordered from Babcock and Wilcox a heavy steel container, which because of its great size, weight and strength was promptly christened Jumbo.

As Groves continues, Jumbo was eventually not used, because even a modest, 250-tons of TNT fizzle would shatter the container, causing more danger than it prevented (and also, presumably, because the Hanford reactor was operating steadily enough that a replacement plutonium pit could be prepared quickly).

From “The Making of the Atomic Bomb” by Richard Rhodes, Chapter 19, p. 686.

This is sometimes the source of confusion: was the atomic bomb dropped because of “institutional momentum” or because of “military necessity”? But that’s a category error. The institutional momentum was to justify the the extravagant cost of the bomb through military necessity. Asking if the bomb was justified because of military necessity is a retrospective, anachronistic view. We think the planners needed a good military reason to drop the bomb. In reality, the needed a good reason to not drop it.

From “Five Days in August” by Michael Gordin, Chapter 3, pp. 39-40.

The discussion of the order and Spaatz-Handy anecdote here is heavily based on Michael Gordin’s “Five Days in August”, Chapter 3, pp. 49-52. You can find a primary source for this incredible quote here.

From “Five Days in August” by Michael Gordin, Chapter 5, p. 97 and Chapter 6, p. 111. Gordin mentions that the one serious scholarly source on the topic is Bernstein’s “The Perils and Politics of Surrender: Ending the War with Japan and Avoiding the Third Atomic Bomb”. I should check it out, so should you.

From “Five Days in August” by Michael Gordin, Chapter 5, pp. 92-95 for a harrowing retelling of the Nagasaki mission, where everything that could go wrong went wrong.

The following four quotes are taken from “The decision to use the atomic bomb and the architecture of an American myth” by Gar Alperovitz, Chapter 27-28, pp. 329-334.

Whether the Soviet nuclear bomb is mostly the result of intelligence or physics is another hotly debated topic. My view, based on this document and Halloway’s Stalin and the Bomb: while the Soviets had ample access to Manhattan Project data through the atomic spies and considered it highly valuable, Soviet physicists re-did a considerable amount of work to check whether the intelligence was correct. The main bottleneck for the first atomic test was not design but plutonium production, which no amount of intelligence can speed up. While the first Soviet bomb, RDS-1, was indeed a copy of Fat Man, on Beria’s insistence, the Soviet atomic physicists immediately developed their own independent designs for deployment, with RDS-1 being dubbed a “political bomb” and promptly abandoned as a design dead-end.

The Baruch Plan got pretty close to this vision being implemented, but extremely obvious problems got in the way: how do you make the only nuclear power get rid of their hard-earned atomic bombs? The political advantage of being a nuclear singularity is hard to resist, so is the political disadvantage of not having nuclear weapons.

I read about this in one of the strangest books I have ever laid hands on: “Megawatts and Megatons”, by Richard Garwin and Georges Charpak. A book for general audiences that aims at telling you, uh, everything you could possibly want to know (or did not want to know, for that matter) about nuclear topics. That includes the effect of Doppler broadening on U-235 fission cross-section (with figures), “Rubbiatrons”, fast neutron reactors, mutually assured destruction, and the Strategic Defense Initiative, with no details spared. A fascinating, if unhinged, read. Anyway, here is the relevant passage, on p. 284, regarding how the Soviets might want to bypass SDI interceptors:

An estimate, by an official of the American government, of 1800 per year as the number of clandestine airplane landings on United States territory, each containing a ton of drugs, has been published. Even an amateur could work out a simple and affordable response to the grandiose Star Wars [SDI] plan. If the KGB could not do it on its own, it should be possible for it to infiltrate the drug underworld and bring into American cities camouflaged thermonuclear bombs, not necessarily small or light, in order to respond to a preemptive strike by a salvo of local explosions if the situation really became unbalanced.

From the same Wellerstein article (“The Kyoto Misconception”) in “The Age of Hiroshima” edited by Michael Gordin and G. John Ikenberry, on p. 38.

This anecdote is also taken from Wellerstein’s “Would the atomic bomb have been used against Germany?”. You can check out the primary source here.

From “Five Days in August” by Michael Gordin, Chapter 2, p. 35.

From “Five Days in August” by Michael Gordin, Chapter 3, p. 53-54:

“Norman Ramsey […] was very surprised after the Hiroshima bombing to hear Tokyo Rose—the Japanese American English-language propaganda broadcaster—report that survivors of the blast were falling sick and dying in large numbers from a mysterious disease. As he recalled after the war: “In general, our reaction was not to believe the report, to suspect that it was propaganda.””

Although the 1946 incident is far more memorable (the “nuclear screwdriver” is a meme by now), the first Demon Core incident, which killed physicist Harry Daghlian, took place in August 1945.

Some description by witnesses to Trinity, from “The Making of the Atomic Bomb” by Richard Rhodes, Chapter 18, p. 672-675.

Isidor Rabi:

[…] we looked toward the place where the bomb had been; there was an enormous ball of fire which grew and grew and it rolled as it grew; it went up into the air, in yellow flashes and into scarlet and green.

Edwin McMillan:

"When the red glow faded out, […] a most remarkable effect made its appearance. The whole surface of the ball was covered with a purple luminescence, like that produced by the electrical excitation of the air, and caused undoubtedly by the radioactivity of the material in the ball."

This is explored in detail in Barton Bernstein’s article “Seizing the Contested Terrain of Early Nuclear History: Stimson, Conant, and Their Allies Explain the Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb”.

This cat fight described in exquisite details in a DoD report titled: “History of the custody and deployment of nuclear weapons: July 1945 through September 1977”. Go take a look, it is absolutely fascinating.