The AI-Productivity Paper That Fooled a Nobel

A post-mortem of my involvement in the Toner-Rodgers affair

On 16 May, MIT issued a rare public notice disowning Aidan Toner-Rodgers’s viral AI-productivity preprint, for “unreliable provenance, data, and methods”. ArXiv promptly withdrew it. Toner-Rodgers’ preprint had been previously endorsed by Nobel laureate in Economics Daron Acemoglu in the Wall Street Journal.

I am writing this piece because I am a participant in this story, albeit a small one. Weeks before MIT's public statement, I uncovered direct evidence of misconduct in Toner-Rodgers' article: a clear violation of informed consent. The survey explicitly promised respondents that 'all responses to this survey are anonymous,' yet the paper repeatedly links individual survey responses to respondents' identities and externally collected data. This textbook compliance violation should have been caught by MIT before the preprint even went public.

MIT’s attempt at correcting the record, while welcome, is nowhere near enough. First, because it says nothing about what made the paper unreliable, and second, because trusting slick statements based on institutional prestige is exactly how we got Toner-Rodgers’ preprint in the first place. What went wrong, exactly?

We should care. Toner-Rodgers’ work had a significant influence on public discourse surrounding the economic impact of AI and interacted in a disturbing manner with the massive science cuts planned by the current administration. It is probably too late to undo those. But getting the nexus of social media, press coverage, and institutional response right might help us nip the next high-profile case of misconduct before it can do lasting damage.

Contents

MIT’s response: the iron curtain

Social media: too little and too late

What Toner-Rodgers Claimed

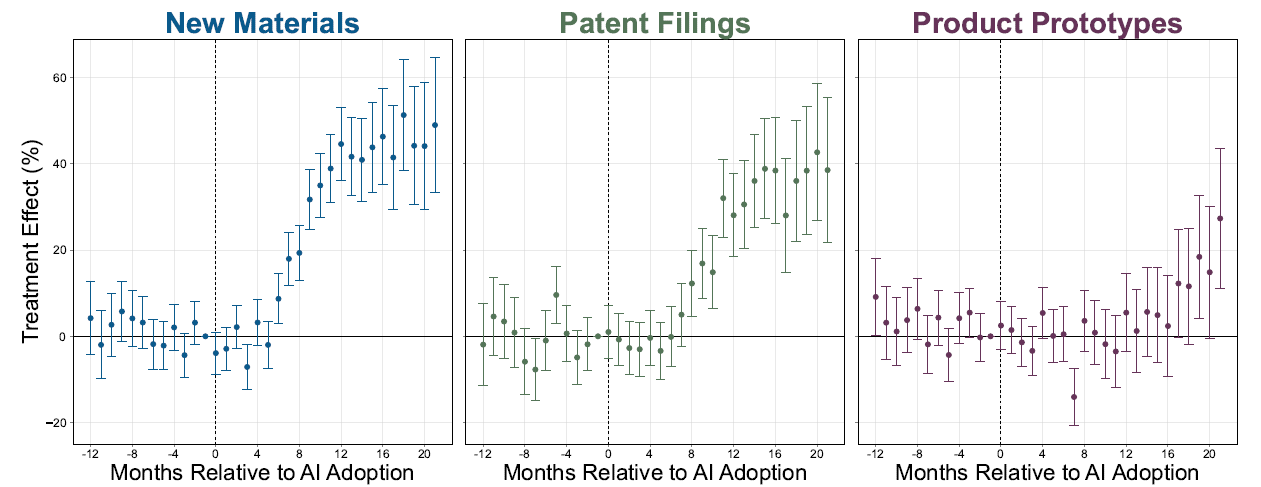

Toner-Rodgers studied the impact of an artificial intelligence tool for material discovery in the R&D department of an unnamed US company. The headline results were, well, a bit too good to be true: researchers using AI discover an astonishing 44% more materials, file 39% more patents and commercialize 17% more products. Other findings had a refreshing, Gladwellian counter-intuitiveness to them. For example, while the bottom third of scientists see little benefit from AI usage, the output of top researchers nearly doubles. Finally, 82% of scientists report reduced satisfaction with their work despite the productivity gains, which proved great for discourse on Twitter (now X).

The paper supports those claims with an impressive methodological arsenal: randomized controlled trial (RCT) model, complete access to the entire R&D pipeline, and a survey of scientists, analyzed using third-party LLM text classification chemical similarity, and statistical testing of scientist productivity, survey response, and patent productivity.

The article was published on Toner-Rodgers’ personal website on November 8, 2024, and later on Arxiv on December 21, 2024. The paper received wide attention both from social media and the press before being retracted from Arxiv on 20 May 2025 following MIT’s notice on the 16.

MIT’s response: the iron curtain of FERPA

It would be easy to blame MIT for stonewalling, of course. We would have another villain besides Toner-Rodgers: one readily available for questions, with a reputation left to burn. Unfortunately, MIT’s invocation of abstract “student privacy laws” is not just PR smoke. Under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), student research misconduct gets lumped with drunken brawls and dorm vapes under the umbrella of “disciplinary proceedings” and are therefore strictly confidential1. Because the preprint was funded by an NSF grant, we might get a one-page NSF Inspector General (NSF-OIG) case close-out memorandum giving us cursory details in a few months or years. Given the recent NSF budget cuts, don’t hold your breath for this one.

The other side of the problem is that despite its impact, the preprint was only a preprint. If it had been published in a peer reviewed journal instead of being unceremoniously dumped on arXiv, it could have received a community critique, editors could have asked for the underlying data, and it could have been retracted after an editorial expression of concern. The entire investigative process would have occurred in public, using the normal mechanisms of scientific publication. This transparency would have made the details of MIT’s disciplinary proceedings irrelevant.

This is not speculation, as the very similar LaCour scandal erupted and resolved within the pages of Science in 2015 along those exact lines. Peer review might rarely catch fraud (Toner-Rodgers’ manuscript was, reportedly, under review at the Quarterly Journal of Economics without any editor sounding the alarm), but peer review does offer a public venue to address it.

The trade-off is that peer review has its own well-known set of problems. Is the ability to address scientific misconduct outside FERPA’s iron curtain worth months of publication delays and submitting to the whims of editors and reviewers? I am not sure. What is certain is that we can’t have the gatekeeper’s cake and eat it: relying on arXiv will inevitably result in shoddy papers staying online, because that’s what arXiv was made to do.

Social media: too little and too late

Some commenters did speak up when the preprint came out. On Twitter (now X), materials scientist Robert Palgrave pointed out sophomoric mistakes in computational materials science techniques used in the paper; metascience advocate Stuart Buck voiced common-sense doubts regarding its implausible scope. But those criticisms were inaudible, drowned in a torrent of fawning commentary, and per their own admission, not concrete enough to reject the preprint wholesale.

Timid skepticism had real consequences. According to the WSJ, MIT’s confidential investigation was started by a critic reaching out confidentially to Acemoglu and Autor after their embarrassing puff piece with Toner-Rodgers. Had the public criticism been louder, the evidence might have emerged publicly instead, instead of the ball rolling silently to MIT, killing any chance to get the full story. This is not a criticism of Dr. Palgrave and Dr. Buck, who should be rightfully recognized for their prescience and willingness to speak up at all, which was more than most, including myself.

After MIT’s disavowal came out, criticism became far more common. Ben Shindel, for example, pointed out more problems with the materials science, more irregularities, more elements that were just a bit too neat and tidy. But without hard proof, we are left filling in the blanks of what actually happened.

Collateral damage

If we limit ourselves to the narrow lens of scholarship, the scientific community might be fine. Toner-Rodgers’ paper had time to accumulate a respectable 50 citations, most in preprints, but it hadn’t yet reached the foundational, field-defining status it seemed destined for. MIT’s response, for all its faults, had the merit to be fast enough to avoid the field-collapsing retractions of a Gino or Hwang. The true consequence of the paper for science, however, might be indirect.

We must look where the paper achieved true success: technologists, opinion leaders, and most worrying of all, policymakers. Here, Brandolini's law ensures that its influence will persist for a long time. The lack of a serious, public scientific debate means that journalists have little to cover beyond the literal words of MIT’s terse release. Quite rationally, they have not covered the retraction with even a fraction of the enthusiasm they put into propagating the original. On May 31, we count a follow-up by the WSJ (who had amends to make, as they published Autor & Acemoglu’s piece), which got picked up by TechCrunch, Yahoo News, and The Economist. Quite short pieces, none adding much to the release. Compare and contrast with the plethoric coverage the original article got in in Nature, WSJ, Time, The Atlantic, Forbes, Planet Money, Macro Roundup, Silicon Valley Product Group, Google DeepMind, Marginal Revolution, The Conversation, International Energy Agency, Technology Law Dispatch…

The real damage might already be done anyway. The main appeal of Toner-Rodgers’ preprint was not its methodology but its implications: a 44% increase in patents held the promise that AI would finally show up in the productivity statistics, by making conventional scientific practice obsolete. The article callously leans on this angle by mentioning that 3% of its sample of (presumably fictitious) scientists were laid off after the introduction of the AI tool, disproportionately “in the lowest judgement quartile”. No wonder that the article resonated with technologists who have a lot of unrealized capital gains hinging on AI, and with think tanks like the American Enterprise Institute, Congressional Budget Office and Congressional Research Service.

The exact idea spearheaded by Toner-Rodgers’ preprint has been used to defend the drastic science cuts of the current administration. Why spend billions on ideologically dubious universities today, the defense goes, when a rack of servers humming somewhere in northern Virginia will do the same for a fraction of the cost tomorrow?

It would be absurd to blame the looting of federal research funding purely on Toner-Rodgers’ work. However, it would not be absurd to say that it contributed to the intellectual climate that led to this looting. In that case, its impact on science might dwarf all previous cases of scientific misconduct combined. We better pray that the tech bros are right, and that the AI scientists are indeed coming for us.

My involvement

With my colleague Nantao Li, I uncovered direct, unambiguous evidence of scientific misconduct in early April, some weeks before MIT’s release. we drafted a detailed report and consulted Dr. Palgrave, who agreed with our conclusion:

Your report here is impressive. It was particularly interesting to read about the logical inconsistencies with the anonymity of the survey, something which I missed when I read his article myself - you make the case very clearly here. I think this point is the most watertight sign that something is not right with the paper.

In the end, MIT’s release caught us by surprise before we could act. Here is MIT’s response after we sent the report, immediately after their release:

Dear Drs. Rasmont and Li,

I write on behalf of MIT’s Committee on Discipline to acknowledge receipt of your email, dated May 16, 2025. While we appreciate your sharing this information, MIT considers this matter closed and has taken all appropriate remedial measures. Student privacy laws preclude any additional disclosure of MIT’s confidential, internal review and there will be no additional statement by the Institute.

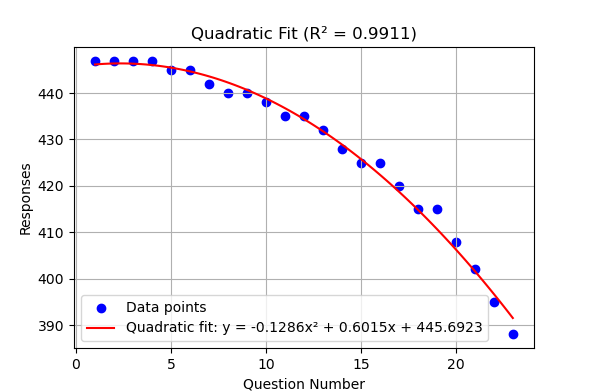

The report is attached below. The smoking gun is a clear violation of informed consent in the survey used in the paper. While it explicitly promised anonymity to respondents ("all responses to this survey are anonymous"), the paper repeatedly links individual survey responses to respondents' identities and externally collected data. It is supplemented by four other more circumstantial concerns that overlap with what other commenters found, including the impossibly broad scope and nonsensical corporate anonymization scheme.

Those problems did not require deep expertise to be found beyond a willingness to read the paper carefully, ignore the seductive numbers presented in the introduction, and use a bit of common sense.

Institutional Accountability

Many institutional safeguards failed for this paper to ever see daylight. Indeed, it mentions in its footnotes, unambiguously, that MIT’s ethics watchdog, the Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (COUHES) approved its survey instrument:

IRB approval for the survey was granted by MIT’s Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects under ID E-5842.

Two possibilities: either this approval was as fictitious as the rest of the data used, or it was real. If it was fictitious, it is a straightforward and easy to detect act of misconduct, and COUHES should have dropped the hammer on the preprint near-instantly. If this approval was genuine, we can ask a few questions, none of which are particularly comfortable for MIT.

COUHES requires a Principal Investigator (PI), usually a faculty member, to sign off its paperwork. Who was this PI, who did not appear as an author alongside Toner-Rodgers?

The survey discrepancy hinges on the informed consent of the subjects. It is possible, although there is no indication of it, that Toner-Rodgers requested a waiver of informed consent, which would make the whole discrepancy moot. Was such a waiver requested, was it granted, and if yes, under what justification?

If, as reported by the WSJ, MIT was tipped off by an external critic about the materials science problems posed by the preprint, it makes things worse. There were many problems in the preprint beyond shoddy materials science that should have been caught internally within days or weeks, not months.

The failure extends beyond MIT as an institution to two of its most prominent faculty: David Autor and Daron Acemoglu, who have so far gotten off too easily in the post-withdrawal media coverage. Their WSJ photo-op with Toner-Rodgers was either a lapse of judgement or a failure of professional diligence; both possibilities are unacceptable for scholars of their stature. While it arrived late in the news cycle (December 29th, a month after the initial wave of interest in mid-November-early December), their endorsement added enormous amounts of credibility.

Lessons learned

The Toner-Rodgers affair exposes failures at many levels of the scientific process. Some of those failures are well-known, structural, and difficult to fix. Others have practical solutions.

Maia Mindel helps us understand why misconduct happened in the first place: the incentives are baked into modern academia and particularly in economics. The econ job market is hypercompetitive, bibliometrics push a publish-or-perish mentality in hiring, and convincing a Nobel laureate to be your advisor is a very reliable way to achieve academic success. Under those circumstances, an unscrupulous grad student has ample incentives to cheat, even at MIT. Furthermore, peer-review is slow, especially in economics, which leads to out-of-peer-review materials (working papers and preprints) flourishing without any of the accountability mechanisms that would have made Toner-Rodgers’ work easy to challenge.

The institutional level is where problems with actionable solutions appear. FERPA should be amended to allow, or ideally mandate, universities to publish investigative reports for research misconduct cases, regardless of whether the perpetrator is faculty or student. This would help resolve which oversight failure at COUHES allowed Toner-Rodgers’ paper to sail through undetected. Congress has already amended FERPA in 1994 to enable more transparency in disciplinary cases for violent or dangerous behavior. It can amend FERPA again to allow transparency in cases of research misconduct.

At the community level, Stuart Buck is on the money: powerful norms of public discourse that discourage open skepticism contributed significantly to the whole debacle. Because so much of scientific life is dependent on being an agreeable, collegial colleague, well integrated in tiny social networks, speaking up against misconduct carries far more risk than staying silent. Being seen as “difficult” or angering a bigwig will damage your career. Dr. Buck and Palgrave, who did speak up, are well-established experts with protective tenure and robust professional standing. The well-meaning people around me pointed out, quite rightly, that I was far more vulnerable as an early career scientist.

This is a tough problem, but it can be partially solved. Generalizing open data clauses in research grants would be a step toward a true culture of “trust but verify” that does not treat questioning underlying datasets as uncouth, even by early-career scientists. This shift is already well underway within funding agencies, but can and should be accelerated.

These reforms matter beyond academic integrity. We have seen how fraudulent research can reshape policy debates before the scientific community catches up. By the time MIT issued its retraction, the damage was done. This problem will only intensify as AI hype accelerates, and policymakers desperately search for evidence to support their decisions. Without independent analysis, we are left to trust the AI salesmen. Already, the CEO of Anthropic is telling journalists that AI could spike unemployment to 10-20% in the next one to five years. This is exactly the type of claim that well-conducted AI-labor research, like a trustworthy Toner-Rodgers preprint, could have helped elucidate.

See for example the statement made by Ohio State University in a similar case of student research misconduct that led to a PhD revocation:

Student education records, including records related to academic misconduct and information about the misconduct that could lead to the identification of individual students, are protected under the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), and cannot be shared by the university.

"The exact idea spearheaded by Toner-Rodgers’ preprint has been used to defend the drastic science cuts of the current administration."

Do you have a source for this?